Me, at Camp Black Hawk in 1992, happy, but uneducated about learning.

The first horses that most of us ride are already trained. When I managed the barn for seven years at my girl scout camp, the horses came to us already trained. Sure, we tuned them up after their winter off, but they came to us knowing all the behaviors we needed them to know. We didn’t even talk about training, or understand the process of learning very well. This phenomenon is pretty much true throughout the horse world, in part because horses live so long and can have multiple stages in their lives, one often being where the horse goes to a beginner or a recreational rider with their skill set already in place to offer the human while they learn the basics of horse care and riding. In effect, because our horses are so long lived, and often so forgiving about their handling and ways of being ridden, training can be something that we understand vaguely as having happened in the past, but don’t truly understand as a process. In addition, because so few people start out with a foal or an untrained youngster, many professionals included, the process isn’t immediately obvious like it is with dog owners who often start with a young puppy who knows nothing about living with humans.

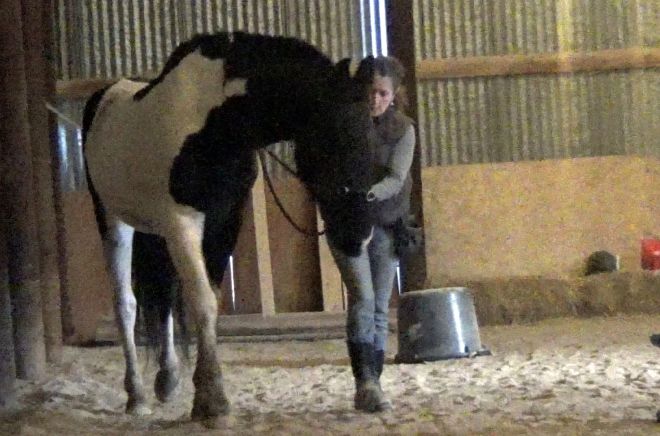

Because of this phenomenon, I often see huge holes in my students’ skill set when they get their first horse that needs active training, rather than passive maintenance of already acquired skills. In particular, I observe that people struggle to understand what to teach when, so I’ve created a basic curriculum to help guide folks working at home. It’s the general progression I use with my own horses and all my students’ horses as well. It allows you to rate where your horse is in their progression of learning and to know where to go next in their education. (This progression assumes a tame horse that wears a halter and is unafraid of humans.)

- Teach your horse to be operant through introduction of target training. If your horse isn’t operant and doesn’t understand they can effect change through their behavior, then you must go back and introduce this step. Even if they seem to have many other behaviors already learned, go back and confirm they are operant and not just passively compliant.

- Go through the process of teaching your horse foundation lessons.

For me this means: Touch a target with your nose, walk forward from a cue on the lead, back up from a cue on the lead, stand quietly in with your head and neck in the center of your chest, aka, “neutral” position, stand on a mat, and offer head down from a cue on the lead.All of these behaviors can be taught from target training and transferred to tactile cues on the lead to avoid learner frustration, but it is very important that the cues transfer from visual to tactile cues as your horse becomes more educated. If they aren’t transferred, you will be limited when you want to begin riding, especially because targets from the saddle throw the horse off balance and badly out of alignment.

Initial teaching of these foundation behaviors should occur in an environment where the horse is totally comfortable and learning is optimal.

- Establish that all of these responses are easy for your horse and can be put together in loops without “extra” behavior creeping in: walk forward – click – back up- click – head down – click, before you move on to rehearsing these behaviors in more challenging environments. (For more information on “loopy training”, check out Alexandra Kurland’s Loopy Training DVD.)

- Expand the context of your horse’s foundation behaviors. Use them in new and ever-widening environments: in the indoor arena, in the outdoor arena, on the road from the barn to the indoor, etc.

- Confirm that you can use the foundation behaviors you have taught your horse to help them balance out emotionally. In the beginning, horse training is essentially energy regulation. Each of the foundation behaviors is there to place your horse in space and offer them an alternative to increasing adrenaline or fear. Being able to help them back away, stand still, move to a mat or lower their head, suggest to them, “Do this for reinforcement rather than just react!”

Once you can use your foundation behaviors to help your horse balance out emotionally, they are safe and ready to move on in the process. This stage of training can take some time, so be patient. - Choose a discipline.

What do you want to pursue? Now that you and your horse have built a system of communication and you both feel safe working in varied environments, it’s time to move on to new skills.

Whether you want to pursue art form dressage, trail riding, horse agility, or working equitation, there will be a whole new set of component skills to teach your horse. Luckily, your horse will now be comfortable in the arena, or the outdoor arena or at a clinic, so you will be able to get to work on teaching the building blocks of your new discipline. And, if your horse gets worried, you know you have the foundation to go back to to help them calm down.

Is your horse not even under saddle yet? Congrats! It’s time to start with the building blocks for ridden work!Helping people identify where they are in this progression with their own horses and helping them acquire the skills to teach each individual piece forms the bulk of my work with my students. In my experience, it takes from 2-4 years to learn the entire skill set as a human, but is a much briefer process to teach to a horse once you understand it yourself, six months to two years, depending on the horse.

Where are you in the progression with your own horse? Do you know where you are going next?

Enjoy the journey.

Did you enjoy this blog? Consider supporting my continued writing through my Patreon site!

Earlier this winter, I did a lot of hiking out in the 100 or so acres behind our farm. There was plenty of soft snow and it wasn’t demanding on cold muscles like accurate arena work. It was a good way to get the blood flowing and as a bonus, I could wear gloves when I fed my horses and while I hiked. I didn’t need extra dexterity on the reins like I do in-hand or under saddle. As we hiked, technically on a “trail ride” as the horses and I were off property, moving in a relative line, I started to think about what a trail ride really is, to the horse, how many owners struggle with taking their horse out alone and what we can take from our daily work to make riding-out possible, safe and fun.

Earlier this winter, I did a lot of hiking out in the 100 or so acres behind our farm. There was plenty of soft snow and it wasn’t demanding on cold muscles like accurate arena work. It was a good way to get the blood flowing and as a bonus, I could wear gloves when I fed my horses and while I hiked. I didn’t need extra dexterity on the reins like I do in-hand or under saddle. As we hiked, technically on a “trail ride” as the horses and I were off property, moving in a relative line, I started to think about what a trail ride really is, to the horse, how many owners struggle with taking their horse out alone and what we can take from our daily work to make riding-out possible, safe and fun.

that he already experiences movement for the joy of it in the pasture. He trots, canters, rears, leaps and gallops up and down his lane, playing with the geldings in the adjacent lane. But my job was to change the old conditioning of movement around people from negative to positive. This was a completely discrete scenario.

that he already experiences movement for the joy of it in the pasture. He trots, canters, rears, leaps and gallops up and down his lane, playing with the geldings in the adjacent lane. But my job was to change the old conditioning of movement around people from negative to positive. This was a completely discrete scenario.

When I named Djinn, I had no idea how completely she would embody her name. I like to name my horses so that they can be represented by one simple symbol, a charm I can hold in my hand. For Djinn, that symbol is a little brass lamp, the same as you would see in a movie about a genie. When I met her, I knew she felt magical and I knew there was something in her that was a little dark. Not dangerous, not evil, but bound up. The name came to me: Djinn, and I knew it was her name. But it was only an intuition.

When I named Djinn, I had no idea how completely she would embody her name. I like to name my horses so that they can be represented by one simple symbol, a charm I can hold in my hand. For Djinn, that symbol is a little brass lamp, the same as you would see in a movie about a genie. When I met her, I knew she felt magical and I knew there was something in her that was a little dark. Not dangerous, not evil, but bound up. The name came to me: Djinn, and I knew it was her name. But it was only an intuition.

I could speculate endlessly about reinforcement histories, repetition, maturity and all the myriad factors that came together for Djinn to be who she suddenly is today. The truth is all of my horses have become pretty spectacular partners at the four year mark, but none of them have made such a sudden and vast leap. Which, when you think about it, is exactly like Djinn all along, to leap wholeheartedly into our conversation, the same way she used to leap away.

I could speculate endlessly about reinforcement histories, repetition, maturity and all the myriad factors that came together for Djinn to be who she suddenly is today. The truth is all of my horses have become pretty spectacular partners at the four year mark, but none of them have made such a sudden and vast leap. Which, when you think about it, is exactly like Djinn all along, to leap wholeheartedly into our conversation, the same way she used to leap away.