Earlier this winter, I did a lot of hiking out in the 100 or so acres behind our farm. There was plenty of soft snow and it wasn’t demanding on cold muscles like accurate arena work. It was a good way to get the blood flowing and as a bonus, I could wear gloves when I fed my horses and while I hiked. I didn’t need extra dexterity on the reins like I do in-hand or under saddle. As we hiked, technically on a “trail ride” as the horses and I were off property, moving in a relative line, I started to think about what a trail ride really is, to the horse, how many owners struggle with taking their horse out alone and what we can take from our daily work to make riding-out possible, safe and fun.

Earlier this winter, I did a lot of hiking out in the 100 or so acres behind our farm. There was plenty of soft snow and it wasn’t demanding on cold muscles like accurate arena work. It was a good way to get the blood flowing and as a bonus, I could wear gloves when I fed my horses and while I hiked. I didn’t need extra dexterity on the reins like I do in-hand or under saddle. As we hiked, technically on a “trail ride” as the horses and I were off property, moving in a relative line, I started to think about what a trail ride really is, to the horse, how many owners struggle with taking their horse out alone and what we can take from our daily work to make riding-out possible, safe and fun.

I was very interested in observing the general change in my horses’ arousal levels as we left our property. All of my horses eagerly volunteer to come out and learn, and all of them are used to working alone, without any other horses. But leaving the home property adds a level of unfamiliarity and a much larger physical distance from the actual herd. Because I am not interested in suppression or force as a tool for controlling behavior, my horses were totally at liberty so I would have an honest read on whether or not they wanted to come along. (Our farm is very secluded, so even if my horses were to go back home on their own, there is really no traffic or road to cross. Other people might not have this set up and will need to make adjustments to ensure safety for their horses.)

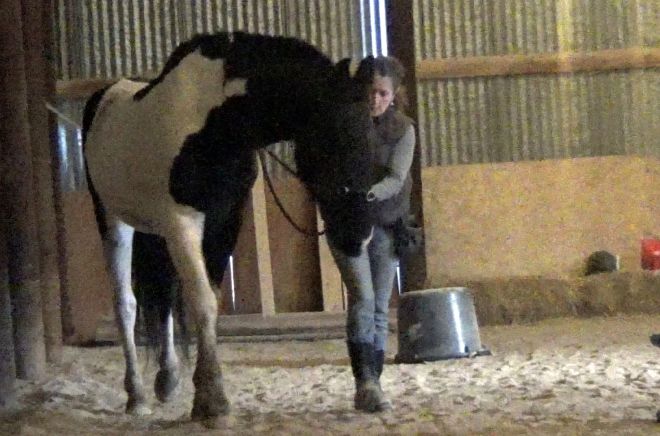

Initially, I took my horses two at a time out hiking. I knew having two together would easily increase relaxation, and I wanted to take advantage of creating positive initial experiences. I had my wife or other training friends come along and each of us was responsible for one horse.

Dragon, Aesop and Sara out on an early winter hike.

With two horses, the hikes were easy and they both stayed quite relaxed, their thresholds nearly identical to when we trained on property. Awesome! But, as we neared home, maybe the last 50 yards or so, they would speed up and canter back into view of the other horses and our barn. It improved with every hike, until it was only the last ten feet as the trail switched from the field to our property, but it was still anxiety. Small things can always turn into big things, so better to address them early. The horses were letting me know where the holes were in their emotional confidence.

The next time I brought Dragon and Aesop into the field, I had a new plan based on what I had observed. Before I took them out, I set up the field with objects I use in training sessions in the indoor arena. I dragged out mounting blocks, some large buckets I use to mark off circles when we longe at liberty, as well as a large plastic spool I got at a dog training store.

My well-loved mounting block.

I set these things up at the entrance to the field, so they were some of the very first and very last things we encountered as we hiked. As we entered the field the first time with the object set up, the change in the horses was measurable. They had felt relaxed before, but now they eagerly walked up to the familiar objects, lining up with the mounting blocks, sometimes moving out ahead to reach an object first and then wait for me to catch up and reinforce. They were focused and thoughtful.

Aesop lining up at the bucket for Sam.

It became very clear to me very quickly, that adding in objects that already had conditioned associations with them and deep reinforcement histories allowed the horses to access their best, most responsive selves immediately. Adding the objects onto our trail walks was like when we got to use our notes for tests in school: everything felt easy and suddenly test taking wasn’t nerve wracking in the least!

Dragon at the mounting block, offering stillness and his back. Lovely!

The objects you use in your everyday training sessions: mounting blocks, traffic cones to mark off circles, and buckets to practice turning around are more than just mundane objects. They become a deep and integral piece of the learning process. What functions do they serve?

- They cue you to stop and ask for a certain behavior from your horse. These objects help order and pattern your training sessions. Trail walks and rides can be long and continuous. Once people start, they rarely stop, which can lead to both the horse or human becoming overfaced as they steadily move into uncharted territory. Using objects along your path can break up the pressure to go, go, go and provide better context for you and your horse.

- They become secondary reinforcers to your horse. Even though these objects are neutral initially, over time, their presence becomes reinforcing to your horse because they so often lead to actual reinforcement. This classical conditioning will help your horse to feel relaxed and eager because working around these objects always predicts good things!

- These objects also cue your horses for certain operant behaviors. If you have done a solid job using objects as targets and context cues in your foundation work with your horse (stand on a mat, line up at a mounting block, trot to the outside of cones, touch your nose to a jolly ball), you have a whole lexicon of visual cues you can take with you on the trail or in new environments. Rather than abandoning all of the familiar and well learned objects, bring them into your trail ride or new environments to help your horse be right!

A short trail ride alone, once we were comfortable thanks to our object work. Heading back toward a mounting block, not pictured.

Riding object to object with Aesop out in the fields.

When we work in arenas, we never ask our horses to go any further from home than they are when they enter the arena. It’s a static space, controlled and safe. But when we head out onto the trail, not only is it an unpredictable environment in terms of wildlife, geographical variation and unfamiliarity; it also takes our horses continually further from home and their herd mates. That’s pretty challenging. Getting our horses used to learning and working in novel environments should be approached thoughtfully and with attention to detail. Intentionally harnessing the power of familiar objects with deep reinforcement histories allows our horses immediate relaxation and context in what can be a fear-inducing situation. It’s just good training.

Do you enjoy reading Spellbound? Head on over to my Patreon page to support me continuing to create stellar content AND see what sort of comprehensive educational materials I have in the works! You will find extra content, my other blog and patron-only rewards there.

that he already experiences movement for the joy of it in the pasture. He trots, canters, rears, leaps and gallops up and down his lane, playing with the geldings in the adjacent lane. But my job was to change the old conditioning of movement around people from negative to positive. This was a completely discrete scenario.

that he already experiences movement for the joy of it in the pasture. He trots, canters, rears, leaps and gallops up and down his lane, playing with the geldings in the adjacent lane. But my job was to change the old conditioning of movement around people from negative to positive. This was a completely discrete scenario.

When I named Djinn, I had no idea how completely she would embody her name. I like to name my horses so that they can be represented by one simple symbol, a charm I can hold in my hand. For Djinn, that symbol is a little brass lamp, the same as you would see in a movie about a genie. When I met her, I knew she felt magical and I knew there was something in her that was a little dark. Not dangerous, not evil, but bound up. The name came to me: Djinn, and I knew it was her name. But it was only an intuition.

When I named Djinn, I had no idea how completely she would embody her name. I like to name my horses so that they can be represented by one simple symbol, a charm I can hold in my hand. For Djinn, that symbol is a little brass lamp, the same as you would see in a movie about a genie. When I met her, I knew she felt magical and I knew there was something in her that was a little dark. Not dangerous, not evil, but bound up. The name came to me: Djinn, and I knew it was her name. But it was only an intuition.

I could speculate endlessly about reinforcement histories, repetition, maturity and all the myriad factors that came together for Djinn to be who she suddenly is today. The truth is all of my horses have become pretty spectacular partners at the four year mark, but none of them have made such a sudden and vast leap. Which, when you think about it, is exactly like Djinn all along, to leap wholeheartedly into our conversation, the same way she used to leap away.

I could speculate endlessly about reinforcement histories, repetition, maturity and all the myriad factors that came together for Djinn to be who she suddenly is today. The truth is all of my horses have become pretty spectacular partners at the four year mark, but none of them have made such a sudden and vast leap. Which, when you think about it, is exactly like Djinn all along, to leap wholeheartedly into our conversation, the same way she used to leap away.

Within a whirlwind twenty-four hours I purchased the mare and foal or “bailed” them out, called on our local and phenomenal animal community who generously raised enough money to cover their transport from Texas to Wisconsin, and found a local farm in Texas willing both to pick them up from the pen and to provide them with a thirty day quarantine and weight gain program. Mare #9668 and foal #9669 would be coming home to Idle Moon.

Within a whirlwind twenty-four hours I purchased the mare and foal or “bailed” them out, called on our local and phenomenal animal community who generously raised enough money to cover their transport from Texas to Wisconsin, and found a local farm in Texas willing both to pick them up from the pen and to provide them with a thirty day quarantine and weight gain program. Mare #9668 and foal #9669 would be coming home to Idle Moon. That’s it. Those are the only two concepts that I need to present to Sistine in order for us to start forging our working relationship. The easiest way to begin her “training”, then, is to set up a very simple contingency where she is sure to succeed because the behaviors I am going to be looking to reinforce are behaviors I have already observed in her repertoire in relation to me, ie, she already does them while I’m there. It’s too grand for me to consider teaching her something novel. I want these first sessions to be easy for her, very low stress and to predict a very high rate of reinforcement. What have I observed that she can do reliably? She always follows me at a walk just behind my shoulder when I walk into paddock with food. Here’s a video of our first training session together:

That’s it. Those are the only two concepts that I need to present to Sistine in order for us to start forging our working relationship. The easiest way to begin her “training”, then, is to set up a very simple contingency where she is sure to succeed because the behaviors I am going to be looking to reinforce are behaviors I have already observed in her repertoire in relation to me, ie, she already does them while I’m there. It’s too grand for me to consider teaching her something novel. I want these first sessions to be easy for her, very low stress and to predict a very high rate of reinforcement. What have I observed that she can do reliably? She always follows me at a walk just behind my shoulder when I walk into paddock with food. Here’s a video of our first training session together: Right now, there is a lot Sistine needs to learn for her own well-being. She is afraid of being haltered so she can’t be led on a rope out of her paddock, yet. She has a bit of a clubbed foot on her left front leg and will need a few years of remedial hoof care plus shoulder stretches to help balance her out. She could use a good brushing. But those skills will come. Without taking the time to introduce her to the idea that she can control reinforcers through her behavior, without letting her confirm that expectation day after day, she won’t be as persistent of a learner. She might shut down, or panic. So, first, I draw her out and allow her to feel successful through easy contingencies that she can fulfill. This is the fun, easy part, watching her begin to light up again. We are building the subtle underpainting that will allow everything later to glow.

Right now, there is a lot Sistine needs to learn for her own well-being. She is afraid of being haltered so she can’t be led on a rope out of her paddock, yet. She has a bit of a clubbed foot on her left front leg and will need a few years of remedial hoof care plus shoulder stretches to help balance her out. She could use a good brushing. But those skills will come. Without taking the time to introduce her to the idea that she can control reinforcers through her behavior, without letting her confirm that expectation day after day, she won’t be as persistent of a learner. She might shut down, or panic. So, first, I draw her out and allow her to feel successful through easy contingencies that she can fulfill. This is the fun, easy part, watching her begin to light up again. We are building the subtle underpainting that will allow everything later to glow.